Palestinians Want Tourists

to Spend Time on the

West Bank

A bid to boost commerce, but Israeli occupation

makes it tough.

by

and

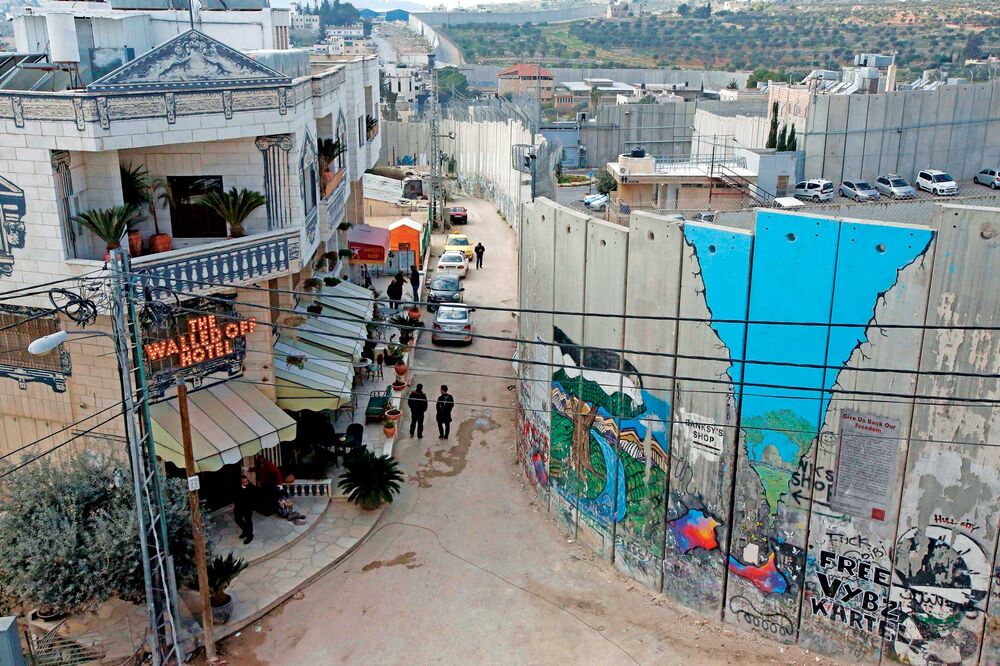

The Walled Off Hotel.

Photographer: Hazem Bader/AFP/Getty Images

And now a message from the Palestinian Authority: Walk in the footsteps of Jesus, enjoy some savory hummus and stuffed grape leaves, and please, please, please spend the night. If you squint, you might not see the watchtowers, barbed wire, and rifle-toting Israeli soldiers.

The Palestinian government is making a push to attract tourists to Bethlehem, Jericho, Hebron, and other historic religious sites—going so far as to call Jesus “the first Palestinian.” While tourism to Israel has steadily increased in recent years, Palestinian-controlled lands—which include many of the major Biblical sites—have seen scant benefit as Israel maintains a tight military grip over the West Bank.

Sure, there’s an annual rush to Bethlehem at Christmas. But even then, most visitors come on day trips to check out Manger Square and the Church of the Nativity, spending little time—or cash. Archaeological jewels such as the Khirbet Bal’ama water tunnel near Jenin and the Sebastia Roman colonnade outside Nablus get scarce traffic. And the new, white-marble Yasser Arafat museum in Ramallah? On a recent weekday afternoon, it had just three visitors. Although political tensions make it tough to attract tourists, Saeb Erekat, secretary-general of the Palestine Liberation Organization, envisions sunbathing and spas on the Dead Sea, bike trails through the Jordan Valley, and Christians flocking to Bethlehem year-round. “If we had an independent state, it would be magnificent,” he says.

Tourism in the Palestinian territories rebounded slightly in 2016, to 2.4 million foreign visitors, up from 2.2 million the previous year, but below the 2.5 million in 2014, government data show. Few, though, remain for the night. Palestinian hotels registered 906,000 stays by foreign visitors in 2016, down from 1.1 million in 2014. In Israel, by contrast, foreigners logged 8.5 million nights in hotels last year. While government figures show Israel got more than $6 billion from tourism in 2016, the Palestinian lands registered less than $1.1 billion in 2014, the most recent data available.

Just as problematic for the Palestinians, the vast majority of visitors arrive via Israel, so Israeli tour operators and hotels get first crack at serving them. Responding to frustrated hoteliers, the PLO issued a report last year on the “annexation of tourism,” charging that Israelis had rebranded some of the most popular West Bank sites as being in the “Holy Land” to obscure their Palestinian identity. Yossi Fatael, head of the Israel Incoming Tour Operators Association, barely disputes the complaint. “All tourists go through our system,” he says. Palestinian areas “are an extension of our product.”

The Palestinians’ ambitions, though, run smack into an infrastructure nightmare. While Jerusalem and surrounding Israeli-controlled towns have European-quality roads, restaurants, and hotels, beyond the walls and fences in the West Bank the potholes grow, and the accommodations suffer. Bethlehem’s Jacir Palace, the only five-star hotel in the area, boasts a grand lobby in the century-old residence of a former mayor, but the paint is peeling, the carpets are worn, and the heat doesn’t always work. While Jerusalem’s Old City is a dense web of narrow lanes dating back millennia, with historic sites such as the Western Wall and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (where Jesus is said to have risen), Bethlehem has little to offer strolling tourists. Manger Square is a barren expanse surrounded by souvenir shops selling cheap olive wood renderings of the Madonna and Child, pearl-inlaid boxes, and T-shirts saying, “I Love Palestine.” Beyond the square, the small old town can be explored in an hour or two, and it pretty much shuts down at sunset. “An odd sense of oppression” pervades the city, says Mary Starkey, a 62-year-old retiree visiting from Britain, after passing through an Israeli checkpoint.

Starkey’s view may have been colored by her lodging: the Walled Off Hotel, which advertises “floor-to-ceiling views of graffiti-strewn concrete.” Recently opened by the London street artist Banksy, the three-story guesthouse stands across a narrow alleyway from a 26-foot-high wall that divides much of the West Bank from areas settled by Jews. “We hope to raise international awareness of how ugly this wall is and in that way contribute to peace,” says hotel manager Wissam Salsaa.

Israel has done a better job of nurturing tourism in a conflict zone. Tel Aviv has cultivated a young, hip vibe with cafe-lined boulevards and surfing on its beaches. There are a growing number of ecotourism ventures in the southern desert and wine trails in the Galilee. And visitors flocking to Jerusalem don’t seem put off by security measures such as armed guards restricting entrance to the Dome of the Rock or off-duty Israeli soldiers roaming the streets with machine guns. “I had mixed feelings when I passed through the checkpoints,” says Leonardo Governatori, a 40-year-old engineer from Italy visiting Bethlehem. “But it’s an experience to see how people live here.”

The bottom line: While tourism to Israel has surged recently, the West Bank hasn’t benefited much. The Palestinian Authority aims to change that.

copied from Bloomberg.com